Direct Listings: The What, The Why and Common Misconceptions

Spotify did it. Slack did it. Many other late-stage private technology companies are reported to be seriously considering doing it. Should yours?

If you are a board member of a late-stage, venture-backed company or part of its management team, you likely have heard the term “direct listing” in the news. Or you may have attended one or all of the slew of recent conferences being hosted by big-name investment banks and others, including tech investor guru Bill Gurley, who recently debated the pros and cons of choosing a direct listing over a traditional IPO.

Before you decide what’s right for your company, here are a few things you need to know about direct listings.

Just What Is a Direct Listing?

For people not familiar with the term, a direct listing is an alternative way for a private company to “go public,” but without selling its shares directly to the public and without the traditional underwriting assistance of investment bankers.

In a traditional IPO, a company raises money and creates a public market for its shares by selling newly created stock to investors. In some instances, a select number of investors may also sell a portion of their holdings in the IPO, although in most instances this opportunity is reserved for very large stockholders or employees and is not made broadly available to other pre-IPO stockholders. In an IPO, the company engages investment bankers to help promote, price and sell the stock to investors. The investment bankers are paid a commission for their work that is based on the size of the IPO—usually 7 percent in the case of a traditional technology company IPO. In a direct listing, a company does not sell stock directly to investors and does not receive any new capital. Instead, it facilitates the re-sale of shares held by company insiders such as employees, executives and pre-IPO investors. Investors in a direct listing buy shares directly from these company insiders.

So now you ask: If my company does a direct listing, does this mean that we don’t need investment banks? Not quite. Companies still engage investment banks to assist with a direct listing, and those banks still get paid quite well (to the tune of $35 million in Spotify and $22 million in Slack). However, the investment banks play a very different role in a direct listing. Unlike in a traditional IPO, in a direct listing, investment banks are prohibited under current law from organizing or attending investor meetings, and they do not sell stock to investors. Instead, they act purely in an advisory capacity, helping a company to position its story to investors, draft its IPO disclosures, educate the company’s insiders on the process and strategize on investor outreach and liquidity.

Why Have Companies Only Started Considering Direct Listings Recently?

The concept of a direct listing is actually not a new one. Companies in a variety of industries have used similar structures for years. However, the structure has only recently received a lot of investor and media attention because high-profile technology companies have started to use it to go public. But why have technology companies only recently started to consider direct listings? A few trends have emerged in recent years that have made direct listings a viable, and sometimes attractive, option relative to an IPO:

The Rise of Massive Pre-IPO Fundraising Rounds: With an abundance of investor capital, especially from institutional investors that historically hadn’t invested in private technology companies, massive pre-IPO fundraising rounds have become the norm. Slack raised over $400 million in August 2018—just over a year prior to its direct listing. Because of this widespread availability of capital, some technology companies are now able to raise sufficient capital before their actual IPO either to become profitable or to put them on a path to profitability.

The Insider Sentiment Against the Current IPO Process: There has been increasing negative sentiment, especially amongst well-known venture capitalists, about certain aspects of the traditional IPO process—namely IPO lock-up agreements and the pricing and allocation process.

IPO Lock-Up Agreements. In a traditional IPO, investment bankers require pre-IPO investors, employees and the company to sign an agreement restricting them from selling or distributing shares for a specified period of time following the IPO—usually 180 days. This agreement is referred to as a “lock-up agreement.” The bankers argue that these agreements are necessary in order to stabilize the stock immediately after the IPO. While the merits of a lock-up agreement can certainly be debated, by the time VCs (and other insiders) are allowed to sell following an IPO, oftentimes the stock price has fallen significantly from its highs (sometimes to below the IPO price) or the post-lock-up flood of selling can have an immediate negative impact on the trading price.

Over time, VCs have gotten companies to chip away at the standard 180-day lock-up period. For example, on many recent IPOs, companies have been able to negotiate for an early release of the 180-day lock-up if the company’s stock price has traded above certain thresholds after the IPO or if the lock-up period expires during a blackout period under a company’s insider trading policy. Despite this, lock-ups haven’t gone away completely.

In a direct listing, there is no lock-up agreement. All of the company’s insiders are free to sell their shares on the first day of trading, providing equal access to the offering to all of the company’s pre-IPO investors, including rank-and-file employees and smaller pre-IPO stockholders.

IPO Pricing and Allocation. In a traditional IPO, shares are often allocated directly by a company (with the assistance of its underwriters) to a small number of large, institutional investors. Traditional IPOs are often underpriced by design to provide large institutional investors the benefit of an immediate 10-15 percent “pop” in the stock price. Over the past few years, some of these “pops” have become more pronounced. For example, Beyond Meat’s stock soared from $25 to $73 on its first day of trading, a 163 percent gain. This has fueled a concern, particularly shared amongst the VC community, that investment banks improperly price and allocate shares in an IPO in order to benefit these institutional investors, which are also clients of the same investment banks that are underwriting the IPO. While the merits of this concern can also be debated, in instances where there is a large price discrepancy between the trading price of the stock following the IPO and the price of the IPO, there is often a sense that companies have left money on the table and that pre-IPO investors have suffered unnecessary dilution. If the IPO had been priced “correctly,” the company would have had to sell fewer shares to raise the same amount of proceeds.

Because a company is not selling stock in a direct listing, the trading price after listing is purely market driven and is not “set” by the company and its investment bankers. Moreover, since no new shares are issued in a direct listing, insiders do not suffer any dilution.

The Spotify Effect: Before Spotify’s direct listing, technology companies hadn’t used the direct listing structure to go public. Spotify was, in many ways, the perfect test case for a direct listing. It was well known, didn’t need any additional capital and was cash flow positive. In addition, prior to its direct listing, Spotify had entered into a debt instrument that penalized the company so long as it remained private. As a result, it just needed to go public. After clearing some regulatory hurdles, Spotify successfully executed its direct listing in April 2018. After Spotify’s direct listing, Slack (relatively) quickly followed suit. Slack’s direct listing was notable because it represented the first traditional Silicon Valley-based VC-backed company to use the structure. It was also an enterprise software company, albeit one with a consumer cult following.

Combine all of these trends and mix in some prominent VCs writing about the benefits of the structure, the media picking up the story and running with it, and even the big investment banks pushing the structure—and the rest is history: Direct listings have now become the hot topic for many late-stage private technology companies considering going public.

Debunking Myths and Misconceptions

As advisors to many late-stage technology companies that are considering a direct listing, we keep hearing a number of common misconceptions. Here are the top three:

“Direct listings are a capital-raising event for the company.”

No! This is one big misconception that we are still continuing to hear. A direct listing is not a capital-raising event for the company. If your company needs additional capital at the time of its IPO, a direct listing is likely not the right structure for your company. And as we discuss in “How to Prepare for a Direct Listing—Best Practices,” although the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission recently rejected an NYSE proposed rule change to allow for a company to raise capital and do a direct listing at the same time, we expect significant regulatory developments in the near future that will give companies more flexibility to pursue alternatives to a traditional IPO.

“I want to do a direct listing because there is less due diligence required.”

Also no! For companies considering a direct listing, limited investment banker due diligence should not be a reason to choose a direct listing over a traditional IPO. That’s because the investment banks and their legal counsel put companies through the exact same due diligence process as in a traditional IPO. They do this in order to protect themselves from liability if a court were to determine that they acted in the capacity of an underwriter. Moreover, a company and its directors and officers are subject to the same liability as in a traditional IPO, so companies are well served by going through the same stringent due diligence process, which serves to protect the company and its officers and directors from liability.

“The direct listing process is totally different from an IPO.”

(Mostly) No! While there are certain aspects of a direct listing that differ significantly from a traditional IPO, the process for each of these transactions is actually quite similar. A company doing a direct listing still selects investment bankers (they are just called “advisors” instead of “underwriters”), holds an organizational meeting, prepares an S-1 registration statement, goes through the same lengthy SEC review and comment process, and has the same liability exposure.

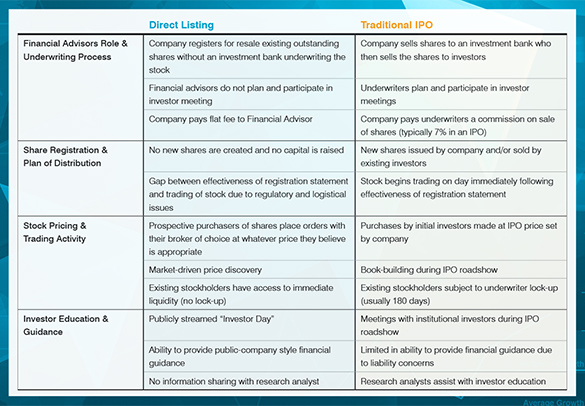

Table 1: How is a Direct Listing Different From a Traditional IPO. Click image to enlarge.

IPO vs. Direct Listing: What’s Right for Your Company?

The high-profile public market debuts of tech unicorns Spotify and Slack are encouraging many late-stage, venture-backed technology companies to consider whether a direct listing makes sense for them. While a direct listing offers many benefits, the structure does not make sense for every company. In this article, we explore the pros and cons of direct listings relative to a traditional IPO and outline some key considerations before choosing this structure.

The Positives

If your company is fresh off a big fundraising round, doesn’t need additional capital and is generating cash flow, then a direct listing may just be right for you.

Direct listings offer companies a number of key benefits:

Equal access to all buyers and sellers: In a direct listing, company insiders are not constrained from selling or distributing their pre-IPO shares by a lock-up agreement. They are free to sell their shares whenever and for whatever amount they want. Moreover, unlike in a traditional IPO, the shares in a direct listing are not allocated by the company to a small number of institutional investors. Instead, investors of all shapes and sizes (yes, even your grandfather and grandmother) can participate at the same time. As discussed below, the large investment banks have also not yet gotten comfortable with involving their research analysts in a direct listing process. Accordingly, unlike in a traditional IPO, companies in a direct listing have been unable to share detailed forward-looking projections with these research analysts. Instead, in a direct listing, companies have issued public-company-style guidance that is available to all investors. Moreover, since the investment banks are not able to set-up and attend investor meetings, companies that have pursued a direct listing have opted out of the traditional IPO roadshow, which consists of a one-to-two-week series of one-on-one meetings between the company’s management team and the large institutional investors buying in the IPO. Spotify and Slack, for example, chose to educate their potential investors by holding an “Investor Day” via live streaming, opening access to a broader base of investors.

Market-based price discovery: In a traditional IPO, the price for a company’s stock is determined based on demand from a small number of large institutional investors for a limited supply of a company’s shares (often only representing 10-20 percent of the entire company). This scarcity in supply results in a stock price following an IPO that isn’t necessarily reflective of what a purchaser of the stock would pay for the shares if more shares were available in the open market. This explains the stock price decline that companies often experience in advance of the lock-up expiration. In theory, a direct listing allows for true market-based discovery since all of a company’s shares are available for sale and purchase on the first day of trading.

Lower investment banking fees: While there is still a bit of mystery around how investment bankers charge for their services in a direct listing, the fees are generally lower than if the company were to do a traditional IPO. To get a sense: Spotify did its direct listing at a $29 billion market capitalization and paid $35 million in advisory fees; Snap went public at a $24 billion market capitalization and paid $85 million in underwriting fees. Slack did its direct listing at a $16 billion market capitalization and paid $22 million in advisory fees, while Lyft went public at a $24 billion market capitalization and paid $64 million in underwriting fees. Due to the more limited role that investment banks play in a direct listing, there is no need to have a large group of banks advising on a direct listing. This results in smaller overall fees being split amongst a smaller group of investment banks.

Similar to an IPO process with a bit less IPO-related documentation and process: A company doing a direct listing still selects investment bankers, holds an organizational meeting, prepares an S-1 registration statement, goes through the same lengthy SEC review and comment process, and has the same liability exposure. Despite all these similarities in the process, there are a few things that are streamlined in a direct listing. For example, you do not need to negotiate and enter into lock-up agreements and an underwriting agreement, and you do not need to go through the FINRA review process.

The Downsides

Despite all the positives, a direct listing is not for every company. Here are *some* of the downsides to consider if your company is thinking about doing a direct listing:

A direct listing is NOT (currently) a capital-raising event: One big misconception is that a direct listing is a capital-raising event for the company—like a traditional IPO. It is not. Companies doing a direct listing aren’t currently raising capital. Even with massive pre-IPO fundraising rounds, many technology companies still need to raise additional capital in their IPO. There have been many instances of high-profile technology companies that have raised a lot of money prior to an IPO and still opted for a traditional IPO structure over a direct listing, including Uber, Lyft and Pinterest. Not being able to raise capital in a direct listing probably forecloses this structure for many technology companies, especially those that are not yet profitable or that do not have a clear path to profitability. Companies that do direct listings can raise capital in a follow-on offering afterward but if the company’s stock price trades down following the direct listing, it may be unable to execute a transaction or have to do so under non-ideal terms. And as we discuss in “How to Prepare for a Direct Listing—Best Practices,” although the SEC recently rejected an NYSE proposed rule change to allow for a company to raise capital and do a direct listing at the same time, we expect significant regulatory developments in the near future that will give companies more flexibility to pursue alternatives to a traditional IPO.

No ability for the company and its board of directors to set the price for the shares or control investor allocations: If your company or board of directors wants to set the price of the shares sold and choose the investors that will buy shares in the offering, then a direct listing isn’t for you.The trading price of the stock following the direct listing is completely beholden to the whims of the market. Moreover, companies can’t pick and choose which investors they want to allocate the shares to. Unlike a traditional IPO, where companies have a say in the allocation of shares, and are able to place the shares with long-term, high-quality institutional investors, companies in a direct listing will have a stockholder base composed of any investor that decides to buy the shares on the open market.

No research analyst education process: In a traditional IPO, companies spend significant time with their investment bank research analysts that will cover the company and its stock following the IPO. Ensuring that these research analysts have a clear understanding of a company’s business is critical as the research that these analysts publish can have a significant impact on a company’s stock price. By all accounts, the process of spending time with the research analysts and building a forward financial model that has been vetted with the research analysts is very useful for companies and allows analysts to build deep familiarity with the companies they are covering. Unfortunately, due to regulatory restrictions that limit what can be shared with research analysts that are not a part of your underwriting syndicate, the investment banks have not yet gotten comfortable with allowing their research analysts to participate in a direct listing. Instead, both Spotify and Slack issued public-company-style financial guidance shortly before their IPO. As a result of the research analyst limitations, companies that do a direct listing are deprived of the valuable exercise of spending time educating the analysts as they would in a traditional IPO process. Moreover, while a company that is very well known may draw research analyst coverage regardless of whether their investment bank was engaged in a direct listing, companies that are less well known that try to do a direct listing may not get research coverage.

Need to create a liquid market for your shares on the first day of trading: There is a lot of uncertainty in a direct listing because it is unclear who will sell and buy shares on the first day of trading. In a traditional IPO, you know who the buyers are and the bankers have a good sense of the trading patterns of your IPO investors in the after-market. In a direct listing, that certainty goes out the door and the market for your shares will be limited by the number of shares that your insiders choose to sell on the open market. An illiquid market on the first day of trading could result in negative consequences for the stock price. Accordingly, companies need to spend a lot more time educating their insiders, including employees, about the direct listing process and how to sell shares, if they so choose, immediately after the stock begins trading. Also, some of the company’s founders and venture capitalists will likely need to sell on the first day of trading to create an active and liquid market for the shares. Finally, the employee education process needs to occur much earlier than it otherwise would in a traditional IPO. Since employees can trade on the first day of trading, the shares need to be prepared for sale, and employees need to be educated about issues like insider trading prior to the first day of trading.

Lots of heavy lifting by management to educate investors: Because the investment bankers in a direct listing are not involved in setting up and attending investor meetings and with no traditional roadshow and research analyst modeling process, the onus falls on the company’s management team to take control of, and run, the investor education process. Companies that do not have a management team that is experienced with navigating the complex public offering landscape may be better served by a traditional IPO, in which the investment bankers are able to assist with the investor education process.

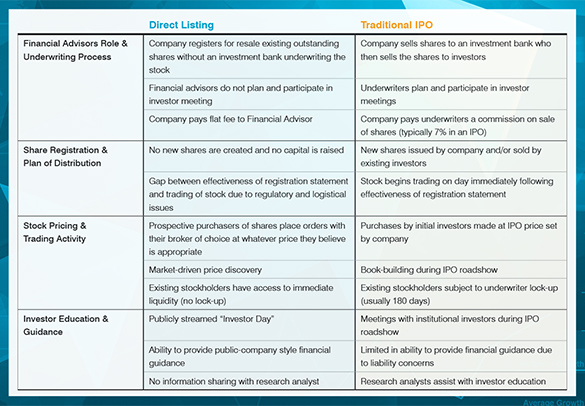

Table 2: The Pros and Cons of a Direct Listing. Click image to enlarge.

How to Prepare for a Direct Listing — Best Practices

Assuming you’ve already weighed the pros and cons and decided that a direct listing is right for your company, we’ve put together a list of a few must-do items to ensure everything goes as planned prior to listing your stock directly.

- Review your financing and organizational documents: This is an easy first step. In order to facilitate a direct listing, your financing and organizational documents should provide for the preferred stock to convert to common stock and for other preferred stock terms to terminate upon a direct listing. Unfortunately, most financing and organizational documents for venture-backed companies provide for the preferred stock to only convert, and for other preferred stock terms to terminate, upon an underwritten IPO. In addition, sometimes the conversion of the preferred stock is conditioned upon the company achieving a minimum IPO price. Since a direct listing would not meet the definition of an underwritten IPO, companies should consider amending their financing and organizational documents in order to preserve flexibility for a direct listing. We have started to work with many of our clients to review and, oftentimes in connection with a financing round, modify their financing and organizational documents to preserve flexibility to do a direct listing.

- Consider a fundraising round before your direct listing: Because your company will not be raising capital in a direct listing (at least not yet), if it still needs additional capital, you should consider doing an equity financing between six and 12 months ahead of the direct listing. The financing should be sufficient in size to carry the company through profitability. Ideally, the financing would include traditional IPO investors, which will help to both create liquidity for the company's shares on the first day of trading as a public company and allow those investors, who will also likely be purchasers of shares in the direct listing, to familiarize themselves with the company.

- Facilitate price discovery by removing transfer restrictions (*don’t do this without consulting with counsel and your investment bankers): In order to create liquidity on the first day of trading and facilitate price discovery, especially if you anticipate issues with liquidity, it may help to create an active secondary market for your company’s shares in advance of the direct listing. One way to do this is to remove the transfer restrictions that typically exist in a venture-backed company’s existing financing, organizational and equity documents. This is one of the tools that Slack considered in order to create a liquid market in the stock prior to its direct listing. Spotify had an active trading market for its shares prior to the direct listing.

- Investor and research analyst education: With no underwriting support from investment bankers and no formal research analyst education and modeling process, it is critical for management to be heavily involved in investor and analyst education and to own the process. We would encourage companies to design an extensive marketing plan six-to-12-months ahead of the direct listing. You don’t want to start your direct listing without having spent significant time with the investors and research analysts that are active in your company’s space. While most of our clients that are doing a traditional IPO outsource their investor relations (IR) function to an external IR firm, we would strongly encourage companies considering a direct listing to hire a strong internal IR person to assist in positioning and with investor introductions and education.

- Educate your existing investors and employees: As discussed above, it is very important to facilitate a liquid market for the stock on the first day of trading. In order to do so, it is critical for a company to educate existing investors and employees about the direct listing process, including how shares may be sold on the first day of trading. As part of this process, the company should seek to gain a good understanding of selling interest from existing investors. Founders and VCs also must be willing to sell on the first day of trading in order to create an active market for the shares. This education should come early in the direct listing process—much earlier than what you would see in a traditional IPO.

I Want the Benefits of Both a Traditional IPO and a Direct Listing: Are There Any Other Options?

Based on discussions we have had with prominent investment bankers that work on technology IPOs and direct listings, we think there’s a lot more innovation to come. There have been many discussions about alternative IPO mechanisms and changing the SEC’s current rules to allow for a non-traditional IPO. And although the SEC recently rejected the NYSE’s proposed rule change to allow companies doing a direct listing to raise capital at the same time, the NYSE has stated it remains committed to evolving direct listings options. We expect significant regulatory developments in the near future that will give companies more flexibility to pursue alternatives to a traditional IPO.