“Reasonable” and “adequate” seem like benign terms — until you have to litigate using them as a standard for adequate data security. Over the coming years, the definition of “reasonable security” (and the alleged failure of companies to maintain that standard) will likely be much debated and litigated, costing companies millions of dollars due to the difficulty of agreeing and evidencing this level of safeguards. The only apparent certainty of a “reasonableness” standard in California is that the plaintiffs bar will sue to find out which combination of security controls (or lack thereof) will determine victory for the inevitable onslaught of class action cases.

“Reasonable” and “adequate” seem like benign terms — until you have to litigate using them as a standard for adequate data security. Over the coming years, the definition of “reasonable security” (and the alleged failure of companies to maintain that standard) will likely be much debated and litigated, costing companies millions of dollars due to the difficulty of agreeing and evidencing this level of safeguards. The only apparent certainty of a “reasonableness” standard in California is that the plaintiffs bar will sue to find out which combination of security controls (or lack thereof) will determine victory for the inevitable onslaught of class action cases.

Most data protection laws and regulatory agencies have historically lacked specificity regarding the minimum necessary controls for adequate data security. For example:

- The European Union General Data Protection Regulation requires an “adequate” level of data protection but offers no explanation or definition for the term.

- In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule for healthcare and the Safeguards Rule for financial services have been among the most prescriptive, and Massachusetts has led the way among states, providing 18 specific standards for protecting personal information (see MA regulations 201 CMR 17.00, in effect for almost a decade).

- The Federal Trade Commission considers the collection of personal information without providing reasonable security to be an unfair practice, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit’s decision to vacate the commission’s order against LabMD in 2018 showed the legal challenges raised by an imprecise standard; the court found that the FTC’s requirement for “LabMD to overhaul and replace its data-security program” was unenforceable because of an “indeterminable standard of reasonableness.”

Consequently, many information technology organizations have focused instead on aligning their operations with recognized security frameworks such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 27001, Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and others.

As states begin to impose more prescriptive, stringent standards for heightened security for the personal information of their residents, companies must determine how to define and maintain reasonable security or face greater consequences, including a private right of action. This article looks at two states that have recently passed legislation that follows Massachusetts’ lead, providing greater detail regarding what is meant by “reasonable security,” in a trend that shows no signs of slowing. While the term may be interpreted slightly differently across state lines, there are several commonalities, as shown through the examples given below.

Greater Clarity from Coast to Coast

New York

Last year, New York enacted the Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (SHIELD Act), amending the state's data breach notification law. The SHIELD Act introduces significant changes, including expanding the definitions of “private information” and “breach,” thereby increasing the likelihood that companies will trigger certain requirements under the law. The act, which took effect October 23, 2019, also introduced new “Data Security Protections” to the New York State General Business Law. These new standards, referred to as the “reasonable security requirement,” take effect March 21, 2020, and apply to persons or organizations that hold electronic private information of a New York resident. Under the law, these reasonable security safeguards include:

- Administrative Safeguards– such as designating employees accountable for security; identifying and assessing risk and safeguard sufficiency; and providing security training, service provider due diligence, contracts and periodic program adjustment.

- Technical Safeguards – such as assessing risks in network design, software design, and information processing, transmission and storage; detecting, preventing and responding to attacks or system failures; and testing and monitoring control effectiveness.

- Physical Safeguards – such as detecting, preventing, and responding to intrusions and disposing of private information within a reasonable amount of time after it is no longer needed for business purposes.

California

The groundbreaking California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which took effect January 1, 2020, contains many new or expanded privacy rights for consumers. One of its most impactful new requirements is contained in Section 1798.150, concerning the liability for companies that suffer a breach of personal information due to the failure to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices. Fenwick previously summarized the reasonable security implications of the CCPA, suggesting that businesses benchmark their controls against the 20 Center for Internet Security Controls (CIS Controls), identified by the California State Attorney General as the “minimum level of information security that all organizations that collect or maintain personal information should meet.” These controls relate to monitoring network connections, limiting user and administrative privileges, performing regular vulnerability assessments and updates, and training, among other things. Unlike many other laws, the CCPA includes a private cause of action against the company for failing to maintain reasonable security and incurring a data breach. If a company does experience such a breach and is subject to a private cause of action, it has an opportunity to respond to the allegation and to cure the defect within 30 days from notice of the private right of action.

Critical Actions to Take Now

Companies must recognize the rising bar for security programs and standards and act now to review and strengthen their information security controls.

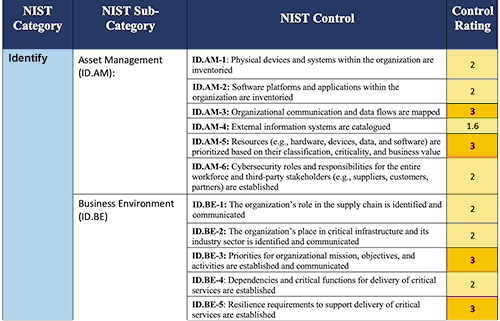

- Create a Security Controls Inventory.Create a centralized inventory of your company’s security policies and controls, organized into categories that align with a recognized industry framework such as ISO, NIST, or the CIS Controls. This inventory can prove instrumental in internal or external assessments, audits or regulatory inquiries, including evaluation of your position in meeting the requirements of “reasonable security” (see next bullet).

Sample Excerpt of Control Inventory

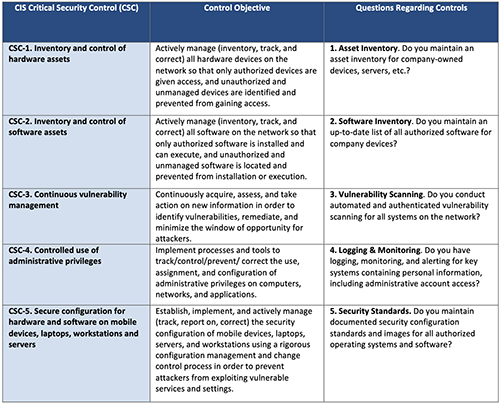

- Assess Your Position Against Reasonable Security.Leverage regulatory guidance and templates, such as Fenwick’s reasonable security checklist and accompanying questionnaire to evaluate key security controls based on the CIS 20, ISO and the New York Data Security Protections. Conducting such an evaluation may provide a “safe harbor” in the event of a data breach and a private right of action under the CCPA.

Excerpt of Fenwick's Reasonable Security Questionnaire

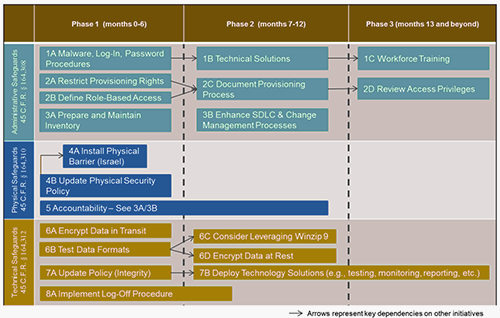

- Remediate Identified Gaps.Based on any gaps identified through the assessment, develop a strategic dashboard to communicate issues and progress to executive management and a roadmap to organize and prioritize remediation activities over the next six to 12 months (or longer, depending on the level of effort required). A remediation plan should identify actions, responsible parties, milestones/deadlines and desired outcomes. Both the assessment and the roadmap can be protected by legal privilege if working with Fenwick’s team of legal and operational experts.

Sample Strategic/Remediation Roadmap