In This Issue

Reducing Cybersecurity Risks to Autonomous Vehicles

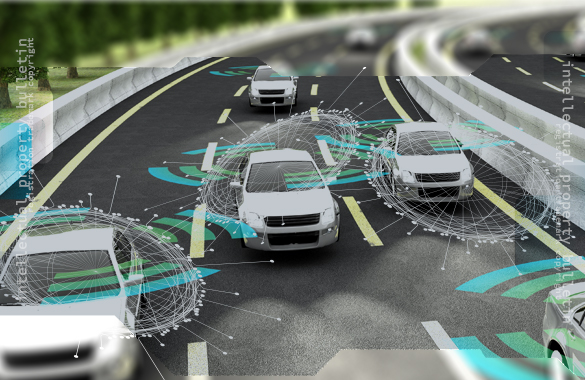

The Department of Transportation is revising autonomous vehicle guidelines it issued in September 2016. Recent comments by Secretary Elaine Chao suggest that the new guidelines might better address safety issues peculiar to these vehicles, including those involving cybersecurity. — John T. McNelis

Forum Shopping Tactics After TC Heartland

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in TC Heartland is widely seen as sharply limiting where patent infringement lawsuits may be filed. But while TC Heartland does raise new obstacles for patent plaintiffs, it remains to be seen whether the limiting effect it has on forum shopping will be as significant as many predict. — Bryan A. Kohm and Jonathan T. McMichael

Quick Updates

Fox v. Aereokiller: Another Nail in the Internet “Cable” Coffin — Mitchell Zimmerman

Stay Tuned: Revisiting NAFTA Could Mean Stronger Protections for IP Owners — Vikram Iyengar

At the Intersection of Civil and Criminal Trade Secret Law: Waymo v. Uber — Meghan Fenzel and Todd Gregorian

Implications of Certiorari Denial in Belmora v. Bayer Consumer Care — Mary Griffin and Vikram Iyengar

Reducing Cybersecurity Risks to Autonomous Vehicles

In June 2017, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao announced that her department is revising autonomous vehicle guidelines issued in September 2016. The new guidelines—which will be released later this year—are expected to address state deference to federal regulations, reporting requirements for accidents and other incidents involving test and production vehicles, human-machine interfaces, consumer education and training, post-crash behavior and crashworthiness.

According to “Chao Ponders Fed Role in Regulating Driverless Tech, ” a June 2017 Detroit News article, Secretary Chao met with auto executives and noted that while the future of autonomous vehicles is bright, “We have a responsibility to ensure that the new technology is safe and secure.” Secretary Chao’s emphasis on “safe and secure” hints that, in addition to the topics mentioned above, the 2017 Guidelines may improve existing guidance by addressing safety issues peculiar to autonomous vehicles. This includes the standardization of road markings and identifying conditions under which autonomous vehicles are not permitted to operate, such as weather restrictions.

Cybersecurity Breaches and Other Risks

It is critical that the security issues covered in the 2017 Guidelines meaningfully address autonomous vehicle data recording and sharing, privacy and cybersecurity. Cybersecurity issues are especially significant. Any software that connects to the internet is susceptible to a cybersecurity attack, and autonomous vehicles will have at least one internet connection. Exacerbating this inherent risk is the fact that some autonomous vehicles are developed by companies that are not original equipment manufacturers. These companies modify a vehicle developed by an OEM by introducing software, sensors and other devices that enable the vehicle to perform autonomous functions. As a result, the autonomous operations are being built using software and hardware that is separate from, or in addition to, software and hardware designed by the OEM. The autonomous functions also use computer networks that were not designed for a high level of automation and remote access. This development bifurcation is a prescription for cybersecurity gaps.

There have been several high-profile automotive cybersecurity breaches in recent years. In one breach, German researchers spoofed a cell phone station and sent fake messages to a SIM card used by a vehicle’s telematics system (the system enabling the long-distance transmission of computerized information). This gave the researchers access to remote convenience features of the vehicle, allowing them to remotely unlock the vehicle’s doors. Several other cybersecurity breaches involved remotely taking control of essential features of a car; one such breach enabled an unauthorized party to take control of various functions of the vehicle by plugging a device into a vehicle’s on-board diagnostic port, where that pugged-in device was able to receive instructions remotely. In addition, in 2015, two unauthorized individuals hacked into a vehicle using its internet connection, and remotely stopped the vehicle on a highway. And in 2016, another vehicle’s WiFi connection was breached, enabling an unauthorized party to take control of its driving systems.

Any type of malware that can put a home computer or smartphone at risk can similarly threaten autonomous vehicles. For example, ransomware attacks that encrypt all of the data on a computing device can be modified to take control of or stop the operation of a vehicle unless payment is made. A user of an autonomous vehicle might not have the luxury of time to figure out a solution to a vehicle that is not operational due to ransomware. These cybersecurity breaches can result in intentional damage to people, the vehicle and other property.

Weaknesses of the 2016 Guidelines

The automated vehicle guidelines issued by the Department of Transportation last year identified cybersecurity as one area of concern, but did not go far enough in addressing cybersecurity risks. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (2016), Federal Automated Vehicles Policy, Washington, D.C. (2016 Guidelines).

The authors of the 2016 Guidelines did understand the cyberattack cat-and-mouse game in which hackers exploit weaknesses in networks as long as they remain unfixed, and then identify and exploit other weaknesses in a serial manner. Accordingly, those guidelines provide a framework for companies to approach cybersecurity problems. They do not propose specific technological solutions, however. Rather, the 2016 Guidelines rely on platitudes and are too tentative. For example, they suggest that manufacturers “follow a robust product development process based on a systems-engineering approach to minimize risks to safety” and employ “established best practices for cyber physical vehicle systems,” but do not provide any meaningful guidance.

A separate report in October 2016 focuses on cybersecurity and provides additional suggestions, such as layered solutions to ensure that vehicles systems are designed to take appropriate and safe actions, even when an attack is successful. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (2016, October), Cybersecurity best practices for modern vehicles, (Report No. DOT HS 812 333), §5. Washington, D.C. While this report provides additional guidance, it is still too tentative to meaningfully assure an adequate level of attention to the cybersecurity risk.

What Kinds of Solutions Should the 2017 Guidelines Identify?

The 2017 Guidelines should more forcefully propose a collaboration among autonomous vehicle manufacturers to address cybersecurity risks. They should also mandate the reporting of any cybersecurity attack to both the collaborative body and the government, to better share and address cybersecurity risks and solutions. In 2015, the automobile industry took a first step in this direction with the formation of the Automotive Information Sharing and Analysis Center, whose charter includes the transparent sharing of vulnerability detection and best practices. However, participation in the Auto ISAC is voluntary, and its recommendations are not binding, even on its members.

The 2017 Guidelines should also require isolated networks: one network for non-essential vehicle operations such as infotainment and telematics functions, and another network for essential vehicle operations. They should also restrict or prevent direct communications between these networks, to make it more difficult for hackers to take control of essential vehicle operations—such as steering and braking—merely by penetrating internet facing software and data—such as a vehicle’s browser, map or traffic data. Isolation may be achieved by implementing a separate physical network, or by using software that effectively isolates the network that controls essential vehicle operations from non-essential vehicle operations.

For software and firmware updates, which are already commonplace in electric vehicles, code signing using secure cryptographic keys—already in use by one vehicle manufacturer—should be required by the 2017 Guidelines.

Other possible cybersecurity solutions include requiring real-time attack detection and a real-time response. For example, when an attack is detected, the vehicle could be safely stopped and a clean version of the software or firmware could be reinstalled. Another solution would be to severely limit access to the internal control/diagnostic bus of the vehicle, which currently provides hackers with direct and easy access to the internal networks of vehicles.

Note to the Industry: Take More Forceful Action or Face Congressional Intervention

Autonomous vehicles are enticing targets for those carrying out cybersecurity attacks. Although the automotive industry has taken some voluntary action, it must take more meaningful steps to adopt cybersecurity measures; otherwise, the industry will face congressionally mandated cybersecurity protections.

For example, in March, the U.S. Senate introduced the Security and Privacy in Your Car (SPY Car) Act of 2017 (S.680, 115th Congress (2017)), a bill designed to improve vehicle security and privacy. If passed, the legislation will require, inter alia, the isolation of critical software systems, i.e., those required for the operation of the vehicle, from noncritical systems.

Forum Shopping Tactics After TC Heartland

By Bryan A. Kohm and Jonathan T. McMichael

The U.S. Supreme Court’s May 2017 decision in TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Group Brands is widely seen as sharply limiting where patent infringement lawsuits may be filed. For nearly 27 years, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit applied a broad test for venue—finding venue proper where an alleged infringer is subject to general or specific personal jurisdiction. Instead, the Supreme Court rejected this longstanding precedent by ruling that venue in a patent infringement case is only proper if the defendant (1) “resides” in the district (for a domestic corporation, its state of incorporation only); or (2) both has committed “acts of infringement” and has a “regular and established place of business” in the district.

While TC Heartland does raise new obstacles for patent plaintiffs, it remains to be seen whether the limiting effect it has on forum shopping will be as significant as many predict. In fact, non-practicing entities will likely engage in a variety of litigation strategies to minimize the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision. This article explores litigation strategies—new and old—that will likely play a role in the post-TC Heartland regime.

Gaming Residence

Many commentators have interpreted TC Heartland to mean that a corporate defendant’s “reside[nce]” under 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b) is the company’s home district (assuming the company’s headquarters is located in its state of incorporation). This is far from settled, however. In TC Heartland, the Court wrote that “residence” means “the State of incorporation” only. Even the notion of incorporating in a specific judicial district does not have much legal grounding. In the eyes of the states (at least the few examined for this article: California, New York and Texas), the process of incorporation does not lend itself to being limited to particular judicial districts in a given state. As such, a question remains as to whether a suit can be filed in any district within the party’s state of incorporation, or whether it must be filed in only one of the districts within the state of incorporation. At least one circuit has held that, for multidistrict states, venue is proper in all districts within that state of incorporation. See Davis v. Hill Engineering, Inc. (interpreting 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c)), overruled on other grounds.

In states with only a single judicial district—such as Delaware, where many companies elect to incorporate—this open question will not be of concern. But approximately half of the states—including California, New York and Texas—are divided into multiple judicial districts. In these states, the opportunity for forum shopping still presents itself. A California corporation with its headquarters in San Francisco, for example, would still be subject to venue in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California—generally considered more plaintiff-friendly than the Northern District of California—or even in the Eastern District of California. Likewise, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas potentially remains a proper venue for patent cases against any Texas corporation, irrespective of where it maintains offices.

Suits Against Foreign Parents

A second implication of TC Heartland is its potential to drive increased litigation against a domestic corporation’s foreign parents as means to obtain favorable venue. In 1972, a unanimous Supreme Court held in Brunette Machine Works, Ltd. v. Kockum Industries, Inc. that patent venue as to foreign entities is not limited by § 1400(b). Instead, as to foreign parent entities, venue was governed by then-existing § 1391(d), providing that “[a]n alien may be sued in any district.” In TC Heartland, the Court expressly declined to “express any opinion” on Brunette Machine Works or the implications of its holding on foreign corporations.

TC Heartland thus provides no guidance as to whether the venue limitations of § 1400(b) can be avoided by simply filing suit against a foreign parent. This is particularly true given that the then-existing venue statute discussed in Brunette Machine Works, § 1391(d), was replaced in 2011. The parallel provision in § 1391(c) now reads that “a defendant not resident in the United States may be used in any judicial district….”

Patent plaintiffs may avoid the new, more restrictive reading of § 1400(b) by suing a foreign parent entity rather than its domestic counterparts. This strategy would place the onus on the foreign defendant to challenge the plaintiff’s complaint and seek a stay or transfer to a different district. In many districts, that burden is not easily overcome. Moreover, many district courts require litigation to move forward even if the defendant timely challenges jurisdiction, venue or the sufficiency of a pleading. Patent plaintiffs, therefore, may file a complaint against a foreign parent (or related entity) in an unfavorable venue as a means of forcing the domestic entity to intervene, or possibly just to create enough hassle to force a nuisance settlement.

Customer Suits

Another method of forum shopping post-TC Heartland is a suit against a customer or distributor of the ultimate target. While TC Heartland limits suits against a corporate defendant to the state of incorporation, and districts in which the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business, a plaintiff set on securing a particular venue may simply find downstream targets to sue in its chosen venue. In the case of an allegedly infringing device, for example, a plaintiff might simply choose to sue the brick-and-mortar retailer in any given district where the retailer sells the device.

This is not to say that the manufacturer-defendant is left with no options. For example, it could still seek a stay or transfer under the judicially created “customer suit” doctrine. Under that rule, “[w]hen a patent owner files an infringement suit against a manufacturer’s customer and the manufacturer then files an action of noninfringement or patent invalidity, the suit by the manufacturer generally takes precedence.” See In re Nintendo of America, Inc.. However, even the customer suit exception has its limits. The exception is not mandatory, and district courts have taken markedly different approaches in determining whether a customer-suit should be stayed in view of a suit involving the manufacturer. In any case, the onus is once again on the defendant to seek a stay and to litigate the case (even in an improper venue) pending the district court’s decision.

Remote Employees

The second prong of § 1400(b) could also be used to forum shop. Aside from the obvious case in which a defendant maintains a brick-and-mortar location where it also has committed acts of alleged infringement, work-from-home employees will increasingly become a means to establish venue. The Eastern District of Texas has taken the lead in addressing this issue. In a recent decision, Judge Rodney Glistrap created a new multi-factor test to evaluate whether the residences of remote employees may be deemed a “regular and established place of business” of their employers. (Full disclosure: The authors represent the party challenging venue in that case). Memorandum Opinion and Order, Raytheon Co. v. Cray, Inc., Case No. 15-cv-1554 (E.D. Tex. June 29, 2017), ECF No. 289. If Judge Gilstrap’s approach is adopted and endorsed, corporations with remote employees for which business expenses are reimbursed (e.g., expenses for telephone and internet use, as well as auto mileage) may be subject to venue in any district where its remote employees reside.

TC Heartland' s Effect on Forum Shopping Remains to Be Seen

Many defendants see TC Heartland as having eliminated their exposure to being sued in far-away districts used by non-practicing entities extract small value settlements. Unfortunately, however, that practice may be far from over.

Quick Updates

Fox v. Aereokiller: Another Nail in the Internet “Cable” Coffin

By Mitchell Zimmerman

Back in 2014, the Supreme Court, in American Broadcasting Companies. v. Aereo, Inc. (Aereo I), shot down a service designed (1) to offer its subscribers internet/mobile access to live network TV programming, (2) without first obtaining licenses, (3) by employing a Rube Goldberg technology that “rented” personal (mini) TV antennas to each viewer, (4) in an effort to dodge a judicial ruling that the service violated the copyright holders’ exclusive right to transmit performances of their programming to the public.

Since then, Aereo—the startup whose streaming service was blocked by the Court—and others have made numerous attempts to tweak the details in ways that would enable an internet cable solution. However, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently handed down yet another ruling that suggests that it will be difficult indeed to find such a solution.

Precursors to the Ninth Circuit Ruling

First, a quick look back. The Supreme Court’s 2014 ruling that Aereo infringed was substantially driven by the Court’s sense that Aereo’s service was functionally equivalent to cable TV, and, therefore, that a contrary result would be inconsistent with Congress’s intent, in the 1976 Copyright Act, to apply copyright restrictions to cable.

Aereo tried a last-ditch response, but that too met with failure in litigation. “Doing its best to turn lemons into lemonade,” the district court observed a few months later in American Broadcasting Companies v. Aereo, Inc. (Aereo II), “Aereo now seeks to capitalize on the Supreme Court’s comparison of it to a CATV system to argue that it is in fact a cable system that should be entitled to a compulsory license under § 111” of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C § 111.

Undaunted by Aereo’s demise, a technologically similar service by FilmOn (formerly Aereokiller) also offered internet access to live TV programming without licenses from copyright holders. Like Aereo, FilmOn attempted to re-characterize itself as a cable system, likewise spawning lawsuits from network copyright owners.

The Ninth Circuit’s Ruling in Fox v. Aereokiller

In the first appellate decision on this topic since the Supreme Court’s AereoI ruling, in March 2017, the Ninth Circuit held in Fox Television Stations. v. Aereokiller that a service that “captures copyrighted works broadcast over the air, and then retransmits them… over the Internet without the consent of the copyright holders,” is not a cable system eligible for a compulsory license.

In effect, the ruling confirmed the Copyright Office’s prior refusal to accept FilmOn’s offer to pay the compulsory license fee for cable systems, and appears to doom this latest effort to offer television programming over the internet without the consent of the networks.

The Ninth Circuit began with an exercise in close statutory reading, first considering and rejecting each side’s claim that the “plain language” of the statute compelled a ruling on its behalf. It finally resolved the issue by deferring to the Copyright Office.

The Copyright Act provides:

“A ‘cable system’ is a facility… that… receives signals transmitted or programs broadcast by one or more television broadcast stations…, and makes secondary transmissions of such signals or programs by wires, cables, microwave, or other communications channels to subscribing members of the public who pay for such service.” 17 U.S.C § 111(f)(3).

The court first addressed Fox’s argument that the “plain text” of § 111 requires that the entirety of a cable system, including the means for secondary transmission of broadcast signals, must be under the ownership or control of the putative cable company. FilmOn would not meet such a requirement, of course, because it does not own or control the internet.

While the court considered the theory “not implausible,” it noted that the “most important difficulty with Fox’s interpretation is that it finds insufficient support in the text of the statute.” Fox. 17 U.S.C. § 111 does not say the transmitter must own the retransmission means it lists, and ordinary language is replete with examples of usage to the contrary. (For example, we may speak of “someone ‘mak[ing] a transmission’ of money ‘by wire’ when he initiates an electronic funds transfer” even though he does not possess or control the wires. Fox.)

What of FilmOn’s position that the statute plainly supports recognizing it as a cable system? “FilmOn first argues that § 111 ‘should be interpreted in a technology agnostic manner.’… making compulsory licenses available to any facility that retransmits,” the court observed, regardless of the means it uses.

The court also took note of numerous considerations tending to undermine the argument that the statute would allow internet-based retransmitters to be deemed cable systems. It indicated that:

- The statute does not simply say, as it could have, that all secondary transmitters are entitled to a statutory license.

- Separate compulsory license provisions (17 U.S.C. §§ 119 and 122) cover secondary transmission by satellite carriers.

- The statutory reference, “other communications channels,” appears to have a technical meaning that does not encompass the internet.

- One could reasonably conclude that “other communications channels” must (as the Copyright Office maintains) be “inherently localized transmission media of limited availability.”

- Powerful arguments suggest that including internet-based services would undermine the balance of interests that 17 U.S.C. § 111 was intended to strike.

- Treating internet-based retransmission services as cable might violate U.S. treaty obligations.

Although the court could “not foreclose the possibility that the statute could reasonably be read to include Internet-based retransmission services,” the panel found that such a reading was not compelled.

To resolve the ambiguity of the statute, the Ninth Circuit turned to the Copyright Office. When a court considers an agency’s interpretation of a statute it administers, it may defer to the agency’s interpretation, the court observed.

The Copyright Office’s interpretation – that to qualify as a “cable system,” a retransmission service must use a localized retransmission medium – finds support in the text, structure and purposes of the Copyright Act, the court held, and denying the statutory license to internet services plausibly maintains the balance Congress sought between the public’s interest in improved access to broadcast television and the property rights of copyright holders.

“The Office’s position is longstanding, consistently held, and was arrived at after careful consideration; and it addresses a complex question important to the administration of the Copyright Act.”

End of analysis and of story. Unless there is a rehearing en banc or Supreme Court review, so ends FilmOn’s run.

Wins for the Broadcast Networks, at Least for Now

It seems fair to question the propriety of deference in areas of law like this, in which the agency’s view does not rest on highly technical matters as to which the agency possesses specific expertise. One way to view Fox might be that instead of interpreting the statute, the panel decided it was good enough to agree to what someone else—the Copyright Office—reasonably thought the law meant. Arguably, such an approach may be seen as an abdication of the judicial responsibility to say what the law is.

The rise of the internet as a major channel of communications, discourse and commerce—and as a disruptor of industries, society and social norms—has repeatedly been accompanied by struggles for control based on copyright law. With two federal courts of appeal having ruled that internet-based services are not entitled to compulsory licenses as cable systems, and with the Copyright Office firmly supporting the network position, the broadcast networks may be able to hold the line regarding exploitation of their content—at least until some as-yet-unanticipated technology opens new ways to challenge the application of copyright law to broadcast content.

Stay Tuned: Revisiting NAFTA Could Mean Stronger Protections for IP Owners

On July 17, 2017, the Trump Administration published its Objectives for NAFTA Renegotiation, following up on its earlier notification to Congress that it planned to renegotiate NAFTA (1994), the first U.S. trade agreement to include IP protections. On July 19, trade officials from the three NAFTA countries announced an aggressive timetable to begin renegotiations on August 16 and conclude by early 2018. The U.S. Trade Representative provided a public comment period titled “Negotiating Objectives Regarding Modernization of NAFTA,” which ended on June 14, 2017. The renegotiation of older trade agreements such as NAFTA could result in the inclusion of strengthened protections for IP owners.

The existing IP provisions in NAFTA of interest to information technology companies include copyright provisions for the protection of software as literary works and data as compilations. In addition, under NAFTA, North American copyright owners of software and sound recordings can prohibit rentals of their products.

NAFTA also provided some patent protection for pharmaceutical and agricultural-chemical inventions, benefiting U.S. pharmaceutical companies. For example, countries must allow product patent protection for drugs and chemicals, for which product patents were previously unavailable. NAFTA also included enforcement requirements, including criminal procedures and penalties for willful trademark or copyright infringement. And, it provided customs departments with the ability to block counterfeits and pirated copyright goods.

On the other hand, NAFTA countries may exclude patents on diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical methods as well as biological processes for the production of plants or animals. Moreover, countries may exclude patents to protect public order, human life and the environment.

The administration’s July 17, 2017 Objectives for NAFTA Renegotiation include accelerated implementation of the WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement (1995), and IP protections for emerging technologies and new methods of distributing products embodying IP for facilitating digital trade. Also included in the objectives are preventing government involvement in IP violations, ensuring that trade agreements foster innovation and promote access to medicines and preventing the undermining of market access for U.S. products through a country’s local laws, e.g., improper recognition of geographical indications or failure to ensure procedural fairness.

The objectives build on the 2015 Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act, which states that the objectives of U.S. trade treaty negotiations are to promote adequate and effective protection of IP and to ensure that trade agreements reflect standards of protection similar to U.S. law. Among measures that could strengthen IP protections are enhanced rules for seizure of infringing goods and an increased ability for plaintiffs to gain compensation for infringement.

In view of its statements regarding foreign piracy of U.S. intellectual property, the administration may seek to include criminal enforcement provisions from domestic laws, such as the Economic Espionage Act (1996), in treaty renegotiations. For example, sanctions for misappropriation of trade secrets to benefit a foreign power could be sought, criminal forfeiture provisions for proceeds of IP-related crimes could be introduced and the ability to gain injunctions against offending parties could be made available.

Additional IP provisions that Canada and Mexico had already agreed to as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) could potentially be the subject of trilateral negotiations. These include (1) extending copyright terms to life plus 70 years; (2) recognizing violations of digital rights management similar to those in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and (3) providing a five-year term for data exclusivity for biologics. The TPP’s five-year minimum period for regulatory data exclusivity for biologics is less than the 12 years granted in the United States under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009.

At the Intersection of Civil and Criminal Trade Secret Law: Waymo v. Uber

By Meghan Fenzel and Todd Gregorian

Although it presents a typical fact pattern for a trade secret claim—a former employee allegedly taking proprietary information to his new job at a competitor—Waymo v. Uber Technologies has become the most closely watched trade secret litigation since the passage of the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016. In February 2017, Waymo, Alphabet’s self-driving car division, sued Uber in federal court in the Northern District of California for trade secret misappropriation, unfair competition and patent infringement.

The case revolves around the alleged actions of Anthony Levandowski, a key engineer on Waymo’s autonomous vehicle team who left to lead Uber’s self-driving car effort and later founder of Waymo. According to Waymo, Levandowski downloaded over 14,000 confidential and propriety files about Waymo’s Light Detection and Ranging remote sensing systems and transferred them to a personal hard drive weeks before resigning in January 2016. The LiDAR system usually sits on the roof of the car and uses a laser to determine how far away an object is from the self-driving vehicle. Levandowski then launched his own self-driving car company, OttoMotto, which Uber acquired in August 2016 for $680 million.

Waymo alleges that with Levandowski’s assistance, Uber used misappropriated documents to develop custom LiDAR systems based on Waymo’s designs. Finding that the evidence indicated that Uber hired Levandowski even though it knew or should have known he possessed the files containing Waymo’s intellectual property, Judge William Alsup granted partial relief to Waymo in the Order Granting in Part Denying in Part Plaintiff’s Motion for Provisional Relief, Waymo LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc. The order barred Uber from using the documents, prevented Levandowski from working on any LiDAR projects at Uber and required Uber to turn over the downloaded materials and findings from a related investigation. In a separate order, Judge Alsup referred the case to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for potential criminal investigation.

Federal trade secret law provides for both civil and criminal causes of action. See Order Regarding Waymo Subpoena to Levandowski, Waymo LLC v. Uber Technologies, Inc (Subpoena Order). Under the Economic Espionage Act 18 U.S.C. § 1832, trade secret theft is a criminal offense punishable by up to 10 years' imprisonment. Both the party that steals the trade secret and the receiving party can be held liable. Judge Alsup referred both Levandowski and Uber for possible criminal investigation.

This has added further complexity to an already fraught discovery process. Levandowski invoked his Fifth Amendment rights, seeking to prevent Uber from producing documents that might incriminate him. This led Judge Alsup to threaten sanctions against Uber. In response, Uber fired Levandowski. When Waymo then sought to compel Levandowski to produce the documents, Northern District of California Magistrate Judge Jacqueline Scott Corley concluded that Levandowski had properly asserted his privilege and denied the motion. See Subpoena Order.

The evidentiary battles have expanded to include Uber’s law firm. The same corporate counsel who represented Uber in the acquisition of Otto continue to represent Uber in the Waymo litigation, adding further complexity.

According to Waymo, Uber’s law firms have copies of its documents that they acquired during the diligence process for the Otto acquisition, and that knowledge of those documents can be imputed to Uber. Uber and its outside counsel argue that the law firms were prohibited from sharing confidential information with Uber during the diligence process, and that it would be inappropriate to impute their knowledge to Uber under the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Droeger v. Welsh Sporting Goods Corporation. Counsel has clarified that in the course of representing Levandowski in arbitration proceedings, it may have come into possession of the downloaded documents. Counsel distinguishes this from its work representing Uber in the acquisition and due diligence process. Invoking both attorney-client and Fifth Amendment privilege as it relates to Levandowski, counsel argues that the firm can hold the documents lawfully.

The legal and business community should pay close attention to the district court's resolution of this case.

Implications of Certiorari Denial in Belmora v. Bayer Consumer Care

By Mary Griffin and Vikram Iyengar

Belmora LLC v. Bayer Consumer Care AG (Belmora I), a significant and long-running trademark and unfair competition case that questioned whether the Lanham Act applies to foreign brands, will not be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court this fall. Given that certiorari was denied on February 27, 2017, foreign trademark owners have standing to sue for unfair competition under the act for the unauthorized use of their foreign brand in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 2004, Bayer, the German pharmaceutical company, applied to register “FLANAX” in the United States, but the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office denied the application based on preexisting efforts by Belmora, a U.S. drug company, to register the mark. Bayer has used the trademark “FLANAX” for naproxen sodium pain relievers in Mexico since the 1970s, and marketed the same product as “ALEVE” in the United States; it owns a trademark for “FLANAX” in Mexico, but not in the United States. Belmora started using the mark “FLANAX” in the United States in 2004 for “orally ingestible tablets of naproxen sodium;” it successfully registered “FLANAX” in the United States in 2005.

In 2007, Bayer petitioned the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board to cancel Belmora’s “FLANAX” mark on grounds that it was confusingly similar to Bayer’s brand of naproxen sodium pain relief products. In 2014, the TTAB cancelled Belmora’s “FLANAX” registration pursuant to Section 14(3) of the Lanham Act, which allows for cancellation of a mark that is being used to misrepresent the source of the goods.

Belmora appealed the TTAB’s decision to U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in Belmora LLC v. Bayer Consumer Care AG (Belmora II), which dismissed Bayer’s claims and reversed the TTAB. The district court based its ruling on its interpretation of the Supreme Court’s Lexmark International, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc. decision, which lays out a two-part test for determining whether a plaintiff has standing to bring a statutory cause of action. Under the Lexmark test, the plaintiff must fall under the statute’s “zone of interest” and must demonstrate economic injury. With respect to the first part of the test, the district court held that Bayer failed to show that its foreign trademark, not used in the United States, represented a “protectable interest.” As to the proximate cause part of the test, the court held that Bayer could not have economic loss for a mark it did not use in U.S. commerce.

Bayer appealed the Virginia decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which held that the district court misapplied Lexmark. See Belmora LLC v. Bayer Consumer Care AG (Belmora III). The circuit court ruled that there is no requirement in the language of Section 43(a), which allows for civil liability against someone who uses a mark that is likely to deceive others, or Section 43(a), that a plaintiff must have used its mark in commerce in order to prevail. The Fourth Circuit vacated the district court’s decision and found that preventing unfair U.S. competition by the “deceptive and misleading use” of foreign marks is within the “zone of interest” protected by the Lanham Act. It also found that Bayer pled sufficient injuries to show proximate cause.

Although the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari means that foreign trademark owners can now bring deceptive and unfair competition claims against U.S trademark owners in certain U.S. jurisdictions, it remains to be seen whether and how other U.S. circuit courts will rule on this issue.