In This Issue

Avoiding the Top 5 Potholes for Autonomous Transportation Startups

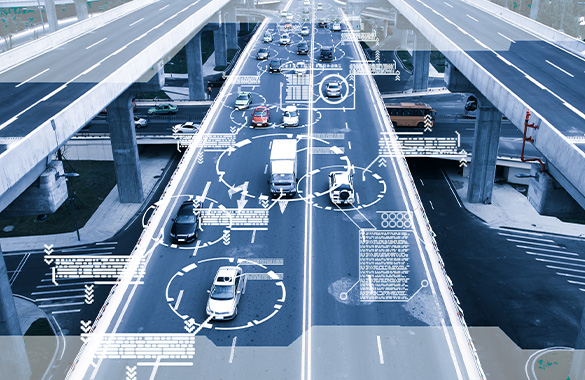

Autonomous transportation technology was widespread at the 2019 Consumer Electronics Show. Startups at the forefront of making autonomous transportation a reality should be careful to avoid the potholes described here. —John T. McNelis

Think You Don’t Have to Worry About Kids’ Privacy? Grow Up!

Five Practical Tips for Reducing Your Risk

The first months of 2019 have seen several key developments in the world of children’s privacy. There have been major enforcement actions, new legislative proposals, and new best practices and guidance issued, both in the United States and abroad. — Lael Bellamy and Joseph Newman

Quick Updates

Copyright Registration After Fourth Estate — Crystal Nwaneri

China at Center of DOJ Initiative to Protect US Companies from Trade Secret Misappropriations — Rebecca A.E. Fewkes

Trailblazers and Lost Einsteins: Senate Discusses Women Inventors and the Future of American Innovation — Nina Srejovic

Will SCOTUS Resolve the Circuit Split on Key Trademark Damages Issue? — Ciara N. McHale and Eric Ball

Avoiding the Top 5 Potholes for Autonomous Transportation Startups

Autonomous transportation technology was widespread at the 2019 Consumer Electronics Show. Advances in object identification, mapping, machine learning, sensing and communication will continue for years as startups and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) work to make autonomous transportation a reality.

Startup companies are well positioned to address some of the problems in the industry but should be careful to avoid the following potholes:

1. Developing cool technology before identifying the market

Some autonomous technology startups have strong technology that the founders want to develop. Startups can make the mistake of developing cool technology before figuring out how it can be used in the market. An example may be a robotics company that decides that it has a clever way of autonomously moving in any direction. The passion and development of this interesting technology may come before identifying the problem to be solved and the scope and feasibility of the market. This results in innovative technology that may not have a strong enough addressable market to warrant further investment.

TIP:Determine gaps in the market where a real need exists and then develop solutions and technology to address them. These gaps can be discovered by talking with potential customers and honing in on their pain points.

2. Publicly disclosing intellectual property prior to executing on a strategy

Innovative companies are understandably eager to publicly announce their ideas. However, without proper advanced planning, a public announcement may adversely affect the ability to secure intellectual property rights. For example, public disclosure of confidential information may result in a loss of trade secret rights. In addition, public disclosure of inventions may immediately result in a loss of patent rights outside the United States and can also potentially compromise U.S. patent rights.

TIP: Develop a marketing plan and preview public disclosures with your attorney to determine the impact they may have on your ability to protect your intellectual property. Use these opportunities to map out the steps you will take to secure your intellectual property rights prior to public disclosure.

3. Contaminating intellectual property at origination

Founders frequently presume that coming up with an idea equates to owning it. This is a mistake and can be very costly for a startup. If the idea originated or was worked on while at a prior employer, the prior employer could potentially assert rights to the intellectual property. Such a claim could arise from seemingly harmless activities, such as using an employer’s copier or network and even using an employer’s computer to access a personal email account. During diligence for a potential investment or acquisition, this could result in the investor or acquirer walking away because of the risk that you do not own the core technology of your business.

TIP:Do not use your employer’s resources when working on your new idea. It is best to work on such ideas outside of your normal hours, at your home, and using your own equipment and services (computer, phone, copier, internet, etc.). If the new endeavor does not relate to the scope of your responsibilities at your current employer, these risks are further reduced, but are not necessarily eliminated. Check your employment agreements for intellectual property assignment provisions. If you think your idea may relate to the scope of your responsibilities at your current employer, you may need to stop working for the employer to minimize the chance of contaminating the intellectual property.

4. Focusing intellectual property strategy only on difficult technology solutions

Startups often feel obliged to protect the key differentiating technology that took significant effort to develop. While the instinct to protect inventions that were difficult to develop is often correct, there are many situations where the technologically difficult solutions are poor patent application candidates. For example, there may be many ways to solve the same problem, enabling others to work around your inventions. In other cases, it may be difficult or costly to detect infringement, or the shelf life of your solution may be only a couple of years given the rapid pace of changes in the technology.

TIP:Identify solutions that can effectively block your competitors, even if they were not particularly difficult to solve. This can be done by examining how competitors are trying to solve the problems that you are addressing in the market and identifying bottlenecks where, if you can obtain patent protection covering the few effective solutions, you can block competitors from implementing those solutions.

5. Having intellectual property that is only based on the current market implementation

A related problem is that startups focus the description in their patent applications only on their current implementation, which limits flexibility during patent prosecution that may occur years after filing. Technology and solutions change, and preparing a patent application that only covers the current solution—in particular where you are continuing to develop the technology—may lead to a patent application that is not relevant in a few years.

TIP:Put yourself in your competitor’s shoes and strategize about how the competitor can design around your patent after issuance. Then you can include those design-arounds in your patent application. For example, you should imagine different ways to approach and solve the problems that your startup’s inventions address and include descriptions of such alternate approaches in the patent application. The additional material provides support for alternate prosecution tactics several years after filing and may also describe the evolved product/service, which allows the patent claims to cover the evolved solution.

Think You Don’t Have to Worry About Kids’ Privacy? Grow Up!

Five Practical Tips for Reducing Your Risk

By Lael Bellamy and Joseph Newman

The first months of 2019 have seen several key developments in the world of children’s privacy. There have been major enforcement actions, new legislative proposals, and new best practices and guidance issued, both in the United States and abroad.

The running theme in all these developments is that companies — especially those who may not intend to or may not be aware that they are targeting children — now need to account for underage users and take necessary precautions to secure their privacy. It’s not sufficient to simply put in a company privacy policy that one’s service is not intended for users under 13; if kids are using a service, a regulator is going to demand the service be kid-friendly.

This article analyzes recent developments and includes steps companies can take right now to protect their business.

Executive Summary

- In the $5.7 million TikTok/Musical.ly settlement, the FTC relied heavily on “reliable empirical evidence” of audience composition when determining which sites are subject to the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA).

- The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) extends additional privacy protections for 13 to 16-year-old California minors, causing a dilemma for U.S. businesses that need to decide whether to single out Californians for special treatment.

- Proposed federal amendments to COPPA would strengthen the law and hold providers accountable if they have “constructive knowledge” that a user is underage.

- The UK Information Commissioner’s Office issued a sweeping new code of practice with strict requirements for providers to protect children’s well-being.

FTC Considers TikTok/Musical.ly “Directed to Children,” Leading to a Record-Setting Fine

On February 27, 2019, the FTC announced a record-setting $5.7 million fine to popular short-form video sharing platform TikTok, formerly known as Musical.ly, as part of a consent order over allegations that the company violated COPPA. The settlement is now the largest COPPA penalty ever obtained by the FTC.

COPPA applies to the operator of any website or online service “directed to children” that collects personal information from children (defined as those under 13 years of age), or any website or online service that has actual knowledge that it collects personal information from children. Unless an exception applies, an operator subject to COPPA must obtain verifiable parental consent before collecting any personal information from a child.

The FTC will evaluate whether a site or service is “directed to children” based on a variety of factors such as: the subject matter of the site or service, its visual content, the use of animated characters or child-oriented activities and incentives, music or other audio content, age of models, presence of child celebrities or celebrities who appeal to children, and language or other characteristics of the website or online service. In addition to these factors, the Commission may also generally rely on other “competent and reliable empirical evidence regarding audience composition.”

The TikTok/Musical.ly app at issue allowed users to create and share short videos with other users. These videos typically featured users lip-syncing to popular music. Musical.ly’s 2018 Privacy Policy stated that “The Platform is not directed at children under the age of 13.” Nonetheless, the FTC, weighing the factors, concluded that Musical.ly was a child-directed service. The complaint stated that creating and sharing lip-syncing videos was a “child-oriented activity” and pointed to the presence of emojis like “cute animals and smiley faces,” “simple tools” for sharing content, songs related to “Disney” and “school,” and kid-friendly celebrities such as Katy Perry, Selena Gomez, Ariana Grande, Meghan Trainor and others.

This is a broad and somewhat striking interpretation, given that this type of content — lip-syncing, approachable design, bright colors, emojis, presence of pop music, etc. — can arguably be found on many sites and services not directed to children. (Take, for example, RuPaul’s Drag Race and its associated app.) While the FTC interpretation here appears to set a worrisome precedent, it’s possible the Commission may be relying less on the “subject matter” factors, and more heavily on other “competent and reliable empirical evidence” of audience composition.

According to the FTC complaint, there was quite damning empirical evidence that Musical.ly staff was aware of the popularity of their platform with children. For example, Musical.ly had received “thousands” of complaints from parents that their children under 13 had created Musical.ly accounts. Meanwhile, prominent press articles highlighted the popularity of the app among tweens and younger children; Musical.ly seemed to acknowledge this themselves when they published guidance stating, “If you have a young child on Musical.ly, please be sure to monitor their activity on the App.” Lastly, the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU) met with Musical.ly’s co-founder and flagged to the company the app’s popularity with kids; when Musica.ly failed to address the issues CARU raised, CARU ultimately referred the case to the FTC.

As Musica.ly likely did not set out to appeal to kids when it launched its service, other companies should view the TikTok/Musical.ly settlement as a cautionary tale. However, if there is a silver lining here, it is that the FTC’s shift toward relying on “reliable empirical evidence” of audience composition should provide a bit more certainty, compared to the “subject matter” factors. A company that does its own due diligence and can show hard evidence that kids are not using its service (for instance, through market surveys or demographic studies) should be in a better position to mitigate its risk.

CCPA: California’s Privacy Rules for Minors Could Be a Major Headache Across the US

The CCPA, set to go into effect January 1, 2020, creates various new compliance burdens on many companies doing business in California. Among them is the requirement that a business may not sell the personal information of consumers they know to be less than 16 years old, without affirmative, opt-in consent from the parent or guardian (or from the consumers themselves if between the ages of 13 and 16). Moreover, under the CCPA, a company will still be responsible if it “willfully disregards” customer ages.

Notably, the definition of “sale” is broadly defined under the law (for example, it could include behavioral advertising or joint marketing promotions); it will be difficult to obtain opt-in consent at scale. As a result, some have argued that, practically speaking, this change raises the minimum age under COPPA from 13 to 16 for California residents only.

The CCPA creates a major compliance burden for businesses, as many global companies do not currently distinguish between users of different states within the United States. To adapt, some companies are considering adding a “state” field to user accounts (potentially based on IP address) and singling out California residents for different treatment. Another option is to raise the minimum age to 16 for the entire United States, though this approach might have a larger impact on revenue. It is also important to note that the law is silent regarding retroactive effect, so it is unclear whether users who are above the age of 13 but under the age of 16 at the time the CCPA is effective may be treated as adults under the law, or if they must go back to being treated as children.

That said, amendments are expected to the CCPA before it goes into effect in 2020. Moreover, the CCPA is very vulnerable to a constitutional challenge based on federal preemption, and the federal government could explicitly preempt the CCPA by passing new legislation, such as the bill described in the next section.

COPPA: New Proposed Amendments

In March 2019, Senators Ed Markey (D-MA) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced a bill to amend and further expand the scope of COPPA. In addition to raising the minimum age to 16 across the United States, the bill text contains several other key provisions:

- “Directed to Children” definition. In addition to looking at reliable empirical evidence of audience composition (like in the Musical.ly case described above), the bill also allows the FTC to look at reliable empirical evidence related to “the intended audience” of the app (emphasis added). In other words, any internal communications discussing what a developer or marketing teams wants their audience to be could be used against them as evidence.

- Continuation of Service required. The service provider must still provide the service to the minor even after deleting the child’s personal information, unless the operator is not “capable of providing such service without such information.” As a result, for a service subject to COPPA, there must be a child-friendly build available: A developer cannot rely on kicking underage players out.

- “Constructive knowledge” regarding individual’s minor status. Similar to the CCPA, providers are required to comply if they have “constructive” knowledge of a child’s age. It is unclear what level of information would satisfy this standard or the extent to which a service provider must investigate users’ ages.

- FTC to establish minimum security standards for all connected devices. The bill also targets connected devices for children, and requires them to adhere to minimum security standards, to be determined by the FTC.

The UK ICO Proposes Sweeping Guidance for Underage Privacy

The United States is not the only jurisdiction with sweeping children’s privacy laws. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that went into effect in 2018 contains parallel protections, and EU member states may set their own minimum age standards (anywhere from 13 to 16 — see this link for more details).

More recently, in April 2019, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) released a 122-page guidance document entitled “Age appropriate design: a code of practice for online services.” The document is out for consultation until May 31, after which the ICO will draft a final version to be laid before Parliament to come into effect before the end of the year. The public has an opportunity to read the code and fill in a survey to give their views.

Looking at the code of practice, there are a great deal of things that, if they remain in the final version of the code, will create substantial new compliance burdens for companies. Three key takeaways are:

- Broader scope of services subject to rules. The burden of proof is on a provider to show its services are not appealing to kids, rather than relying on a standard related to the provider’s actual knowledge. Moreover, online services that have a substantial number of underage users are subject to the rules, even if underage users are an insubstantial percentage of the overall base. This could mean many popular adult-oriented services may have to consider children for the first time.

- Strict transparency/control requirements. The ICO recommends a dynamic and comprehensive privacy notice, designed for kids to understand. Moreover, all settings must be set to “high privacy” by default, with features and notices specifically designed to steer kids toward making good decisions.

- “Targeting” and “profiling” must be off by default. Personalization of services, including using a child’s data to suggest things like in-app purchases, must be opt-in. Previous guidance under COPPA suggested that contextual personalization might be okay without an opt-in, but the ICO rules require that personalization efforts be off by default, unless keeping them on is in the “best interest” of the child.

Five Practical Tips for Reducing Your Risk

The developments above make it clear that children’s privacy is a hot topic, and it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. While much of the law here is in flux, there are a few things companies can do now to prepare:

- Re-analyze your site/services’ appeal to children. The Musical.ly/TikTok case and ICO guidance both emphasize that a service may be subject to the rules even if the developers did not intend to target kids. Keep on the lookout for empirical evidence of your app’s audience composition. For example, see if your marketing team has data regarding the target demographics of your app. Keep up on the news and see if the app is starting to become popular with younger users. Determine whether your app is being featured on any “Children’s” or “Families ” lists. In any case, counsel should be involved in this investigation to preserve attorney-client privilege. If there is any doubt, consider gating users based on age.

- Age-gate the right way. With respect to implementing an age-gate, the FTC has stated that a service provider cannot encourage children to lie about their age or make it easy for the child to circumvent the gate (for instance, by clicking the “back” button and trying again). When implementing an age-gate for a service that is already live, make sure that the gate is presented to existing users as well as new users, and that the language used in the age-gate is appropriate for your app’s audience. Once you have users’ ages, delete any personal information you may have collected from or about underage users.

- Perform privacy due diligence during and after M&A. Musical.ly was acquired by ByteDance Ltd. in August 2018 and merged with the TikTok app under the TikTok name. If you acquire a company, make sure you do thorough due diligence on any privacy issues your target might be bringing along. Acquirers should conduct a post-close privacy assessment to evaluate and remediate any risks. COPPA Safe Harbor programs are slowly gaining popularity with some companies; consider if they might be right for you.

- Train, train, train: Teach your customer service reps to handle underage users. Several privacy laws specifically require employees who handle sensitive data to be adequately trained: It’s important that customer service reps can handle complaints from parents and know what to do when it sounds like a child might be on the other end of a customer support line. Customer support should also keep in close contact with your company’s legal team and flag if they sense that a game might be unexpectedly popular with kids.

- Consider what you can do now to adapt to the ICO guidance. The ICO guidance is not yet binding, but the requirements are extremely strict. Some things you can do to prepare in the meantime include drafting kid-friendly privacy policies or other privacy settings to give a more privacy-protective experience to a child.

These are complicated issues, so companies should work closely with privacy counsel during this period of enhanced focus on children’s privacy and take the necessary precautions.

Quick Updates

Copyright Registration After Fourth Estate

In Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corporation v. Wall-Street.com, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court held in March of this year that a copyright claimant can only commence an infringement suit, unless a limited exception applies, after the Copyright Office has taken action and registered a copyright under 17 U.S.C. § 411(a). That section of the statute states “no civil action for infringement of the copyright in any United States work shall be instituted until preregistration or registration of the copyright claim has been made in accordance with this title.” Despite this language, different courts around the country, like the parties in this dispute, interpreted this language to mean different things.

In this case, Fourth Estate, a news organization, sued Wall-Street, a news website, for copyright infringement when Wall-Street failed to take down Fourth Estate’s news articles after a license between the parties expired. Fourth Estate filed its complaint after submitting applications to the Register of Copyrights, but the Register had yet to act on the applications. Because Fourth Estate did not have a registration, the district court dismissed the complaint and the Eleventh Circuit affirmed.

Before the Supreme Court, Fourth Estate argued that the best interpretation of § 411(a) was the “application approach,” where a claimant is permitted to file suit once they submit the application, materials and fees to the Register. Wall-Street contended that the only approach that made sense was the “registration approach,” where a “registration…has been made” and the Register has given a registration to a claimant. The Supreme Court agreed with Wall-Street, saying the registration approach “reflects the only satisfactory reading of § 411(a)’s text.”

The Court reasoned that registration means “action by the Register” because the alternative reading proposed by Fourth Estate would have made subsequent sentences in the same part of the statute — allowing suit upon refusal of application and allowing the Register to become a party to a suit where registrability is in dispute — superfluous. It found that other provisions of the Copyright Act and various actions by Congress maintaining registration as a prerequisite to suit also supported this reading. The Court was not persuaded by Fourth Estate’s argument that a copyright owner may not be able to adequately enforce her rights, even potentially being barred by a statute of limitations, if she has to wait for the Register’s review period. It explained that Congress addressed these concerns when they made carveouts to § 411(a) and that otherwise the seven-month processing time for an application still leaves ample time for a copyright owner to sue after a decision even for infringement that began before the application was submitted.

This was a straightforward ruling, but it will have a significant impact on all authors that maintain and enforce a copyright portfolio. Although the option was limited to certain jurisdictions, authors could previously apply for a registration when a dispute arose. They will now need to develop and implement a process to proactively apply for copyright registrations if they don’t want to wait seven months to take action (or pay for special handling to expedite registration) should a dispute arise later. This ruling can and should have a significant impact on how businesses that maintain significant copyright portfolios but are less vulnerable to preregistration infringement, such as the news organizations in this suit, approach their copyright registration practices.

China at Center of DOJ Initiative to Protect US Companies from Trade Secret Misappropriation

The U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator submitted its Annual Intellectual Property Report to Congress in February. The report recognizes the economic importance of intellectual property and recommends enforcement policies to protect U.S. intellectual property domestically and abroad. It summarizes the administration’s engagement with trading partners and use of legal authorities, including the U.S. Department of Justice.

One DOJ prosecution initiative is protecting American businesses from commercial and state-sponsored trade secret misappropriation. The DOJ reports 10 recent cases to illustrate this focus. Its FY 2018 prosecutions reveal that trade secret misappropriation is widespread, encompassing all regions of the United States and spanning numerous industries, including finance, engineering, technology, aviation, manufacturing, defense and pharmaceuticals. Another indication that the problem is grave: 81 industries (out of 313 total) are identified as IP-intensive and account for 38 percent of U.S. GDP. Technological innovation is linked to three-quarters of U.S. growth since the mid-1940s, and estimates of the cost of trade secret misappropriation from U.S. firms range from $180 to $540 billion.

In FY 2018, the DOJ prosecuted the following misappropriations:

- Chinese hackers working for an internet security firm that accessed private companies to take sensitive internal documents and trade secrets

- A Chinese intelligence officer attempting the theft of aviation trade secrets

- Scientists taking GlaxoSmithKline biopharmaceutical research for the benefit of a Chinese company

- An engineer taking GE data files of turbine technology trade secrets

- An employee taking circuit board schematics for autonomous vehicles before returning home to China

- An employee taking DuPont trade secrets to a competitor in the enzymes industry

- An engineer placing defense contractor files in a personal cloud account to bring to a private company

- A Chinese manufacturer/exporter of wind turbines taking trade secrets from a U.S. company

- A Canadian citizen taking mining trade secrets to solicit China-based investors to build a competing plant

- Employees taking trade secrets from a competitor

- Chinese state-owned companies taking chemical production technology from DuPont

- Two businessmen conspiring to take trade secrets from a foam material engineering firm for the benefit of a Chinese company

- An employee taking proprietary source code to benefit a Chinese government commission

A common theme among most of these prosecutions is the presence of a Chinese state or business actor.

In 2015, China unveiled its “Made in China 2025 ” plan to make itself into a high-tech leader. It identified 10 industries — including robotics, information and clean-energy cars — that should become globally competitive by 2025, and targeted rapid technological progress for all services and professions in China. The plan received little attention then but has since become a blueprint for U.S. response.

According to the administration’s U.S. Trade Representative, China conducts and supports misappropriation, including unauthorized intrusions into computer networks of U.S. companies to access sensitive commercial information, as part of a larger scheme of actions that burden U.S. commerce. The USTR’s November 20, 2018 Update on China details the recent history of U.S. investigation into China’s practices, China’s refusal to “respond constructively” and the ensuing trade battle, including tariffs targeted at the industries on the “Made in China 2025” list.

Beijing has since replaced the “Made in China 2025” policy with a program that allows greater access for foreign companies. Premier Li Keqiang’s State of the Union-type speech on March 5, 2019, made no mention of the old policy, in marked contrast to previous addresses.

And on March 15, China passed a foreign investment law that bars officials from divulging corporate secrets. The change eliminates conflicts of interest in review panels that foreign companies must pass before establishing plants or beginning manufacturing. The administration views the panels as instruments for taking proprietary information and forcing technology transfers.

China’s current moves may be cosmetic or constitute real change, and resolution of the trade war is apparently on the horizon. How this will affect the administration’s investigation and prosecution of Chinese-sponsored misappropriation is difficult to predict. For now, China remains at the center of the administration’s focus on trade secrets.

Trailblazers and Lost Einsteins: Senate Discusses Women Inventors and the Future of American Innovation

On March 27 and April 3 of this year, the House Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet and the Senate Subcommittee on Intellectual Property held hearings on “Lost Einsteins,” women and underrepresented minorities who do not have equal access to the income-generating and innovation-promoting benefits of the United States patent system.

The hearings came on the heels of a Yale report — and the subsequent reaction to the study — which found that only 10 percent of U.S. patent inventors are female, and that more than 80 percent of patents list no female inventors. (For more on this subject and on the Yale report, see the Fall 2018 issue of Fenwick’s Intellectual Property Bulletin.) The Senate hearing also followed last year’s passage of the Study of Underrepresented Classes Chasing Engineering and Science Success Act of 2018, which directed the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to study and report on the number of patents obtained by women, minorities, veterans and low-income individuals. As stated by Senator Christopher Coons (D-DE), Ranking Member of the Senate IP Subcommittee, “Congress, the PTO, other agencies, the private sector [] need to work together to ensure opportunities for all inventors to patent and commercialize their inventions because talent is distributed evenly across the human genome and yet participation in invention, innovation, and in particular patent protection, is not. That jeopardizes our ability to lead globally and undermines our investments in a brighter future.”

Witnesses at the hearings included inventors, academic researchers, industry counsel and Michelle Lee, former Fenwick partner as well as former Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and USPTO director. Because the USPTO does not collect data on race, veteran status or income of patent applicants, witnesses at the hearings focused their testimony on gender disparities while urging the patent office to collect data on the other underrepresented groups.

In February, the USPTO released the Progress and Potential report, which provided information inferred from the assumed gender of inventors’ names. The study showed that the percentage of women patent inventors reached a high of 12 percent in 2016. The number of patents with at least one woman inventor grew from seven percent in the 1980s to 21 percent in 2016, but the growth rate in recent decades has slowed. In addition, the percentage of patents by either an individual woman inventor or a team of all-women inventors is about four percent and has shown little growth since 1976. The share of women on gender-mixed inventing teams has actually fallen since 1976.

In the House subcommittee hearing, Dr. Ayanna Howard, a roboticist and professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, made a few friends with members of the patent bar by sharing her secret for obtaining patent protection, saying, “I discovered a bit of a trick. Hire a great patent lawyer.” Howard acknowledged that the price tag is not sustainable for most small business owners, however, and pointed out that more resources are needed for those people. She testified to the need for more pro bono assistance for inventors.

While access to patent prosecution resources may be part of the problem, data in the Progress and Potential report indicates that it surely is not the only impediment faced by women inventors. According to the report, the percentage of women patent holders who hold their patents as individuals is roughly equal (about 15 percent) to the percentage of women patent holders who assign their inventions to public research organizations. In contrast, “the women inventor rate on patents granted to business firms is persistently the lowest,” climbing “from only 4 percent in the 1977-1986 period to 12 percent in the last decade.” As stated by many witnesses at the hearings, more data, such as the proportion of women inventors that claim small entity status at the USPTO, is needed to determine whether resources should be focused on pro bono legal assistance to increase female patent participation.

Other testimony at the hearings made clear that a multifaceted approach is needed to address the inequity of opportunity for potential women inventors. Witnesses at the hearing proposed several solutions to the barriers shown by the data. These solutions varied from providing more images of women inventors in the media, supporting California’s new requirement of female representation on corporate boards, addressing the venture capital funding gap and enforcing laws that provide a more welcoming environment to women employees to ensure that women stay in the workforce long enough to develop the expertise to invent. Senator Marcia Blackburn (R-TN) suggested that Congress could take a first step by replacing the term “lost Einsteins” with “lost Marie Curies.”

Will SCOTUS Resolve the Circuit Split on Key Trademark Damages Issue?

By Ciara N. McHale and Eric Ball

A petition for writ of certiorari pending before the U.S. Supreme Court asks the Court to decide whether a plaintiff must prove willful infringement to obtain an award of a trademark infringer’s profits for a violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a). A Supreme Court ruling on the issue would resolve a long-standing divide among the circuit courts and significantly impact the damages landscape for trademark litigants.

In Romag Fasteners v. Fossil, Romag Fasteners — a magnetic snap fastener seller — sued fashion design and manufacturing company Fossil for trademark and patent infringement in 2010, alleging that Fossil was selling handbags with counterfeit snaps bearing the Romag mark. Romag prevailed in a jury trial in 2014, with the jury finding Fossil infringed Romag’s trademark but that the infringement was not willful. After a subsequent two-day bench trial, the trial court held that “Romag [wa]s not entitled to any award of profits as a result of Plaintiff’s failure to prove that Fossil’s trademark infringement was willful.” After post-trial motions, Romag appealed. The case reached the Supreme Court in 2016 on both the willfulness question and a second question as to whether laches barred in whole or in part the patent infringement award. The Court remanded on the second question, leaving the trademark damages question unanswered until now, when it has made its way back up to the justices.

The cert petition asserts that the circuit courts are “sharply divided” on the question the petition raises. On the one hand, the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Eleventh Circuits do not require a showing of willfulness for a plaintiff to recover an award of an infringer’s profits for violation of § 43(a). On the other hand, the Second, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth and D.C. Circuits require that a plaintiff proves willful infringement in order to recover an infringer’s profits. The Federal Circuit also required a willfulness finding in its decision in this case, which is the subject of Romag’s petition. Finally, the First Circuit also requires a showing of willfulness, but only where the parties do not directly compete.

Romag points out in its petition that “[c]ourts, academics, and commentators widely acknowledge the square conflict this case presents,” arguing that this “state of affairs is intolerable for a federal statute that should apply uniformly across the country” and that “[o]nly this Court can break the impasse.”

If the Supreme Court grants the petition and again takes the case, its ruling will likely have a significant impact on litigation of trademark damages going forward, including by shifting the state of the law in several circuits.